Neologisms in times of Alphabet Inc.

The following text is entirely based on the non-scientific stratagem of literature, and in particular, the text is structured around the creation of new words – neologisms – whose greatest ambition is to be credible for the glimpse of an instant, and then probably to evaporate. Conversely, the neologism may actually crystallize, could come to be part of common usage and ultimately introduce a debate in current society, a debate set up with its own very existence. A neologism – in its pure state – is something for which you can’t find an explanation on Google yet, so you have to make sense of it, deducing yet elaborating on a possible meaning. At the same time a new word, in order to function properly, must be able to defer to something already known – that exists in the dictionary – and again, to propose a previously unforeseen possibility or desire. The more the desire pertains to what we have in common as human beings, the more it will succeed in upgrading the dictionary we use. Well, this is “a paradox every musician is quite familiar with. You are inspired by something and would be happy to do just that. On the other hand, you are perfectly aware that this is not an option at all. The only way out is to take the elements that fascinated you and try desperately to form something different with them, preserving a bit of the spirit present at the starting point, shifting it somewhere else. Probably a lot of evolution in art or music happens just through this process.”1

Morestalgia

Recently, a new phrase entered the common language of daily news: foreign fighter. As its use became increasingly pervasive, I began to wonder what motivated – and what drives – some of my peers, born to migrant parents in the suburbs of European cities, to travel to the land of their ancestors in order to receive military training. I wondered, in particular, if one can feel regret for something that one has never really lived, that is, never had direct experience of in the sensible world. Or, to put it simply, can one make a return trip in the total absence of a round trip? I called this feeling “morestalgia” – this specific kind of homesickness – whose sense of pain is similar to that caused by the feeling of envy rather than nostalgia: a feeling of lack – self-translated as loss – whose direct reference is experienced by others. The others, specifically in regard to foreign fighters, are often family members, or at least someone or something one can easily identify as a credible starting point, a seed, a root. Morestalgic human beings are those who have the desire to live an experience they have previously understood as a plausible one, but instead of recalling it from their own past, they substitute it with an immersive navigation experience offered by the web. The past is not actually experienced by those who feel they have lost it, but they can recall it right now – and embrace it again – with a single click. One could say that this is the raison d’être of marketing practices: to create a new desire means to induce a person to perceive an absence (in order to satisfy it with a product). From this point of view the internet is nothing but the amplifier technology of the role played by television in the last century. The structural difference lies in the amount of exposure of humans to data2 and – rather then the actual data resolution – the context within which the data have been produced, especially data symmetrically produced by original or pretending-to-be-real living humans, such as social network contents3: our mind seems induced to process events offered by the screens of portable devices as life lived, and – in doing so – to oust the body from the possibility of performing regular rounds of sensory inspections. Morestalgia can therefore be defined as augmented nostalgia: not only does local mean the exact opposite of virtual4 – more specifically – global becomes the opposite of sensorial5. Isn’t that the reason why revolutions and democracies these days seem to want to change the world’s perception of themselves as events rather than to succeed in improving the living conditions of the human beings who experience them?6In other words, the past sounds safe – even when it’s not – while the future is risky, especially when it seems safe. Therefore, in order to reframe the morestalgic feeling of the foreign fighters, one question arises: is any past we have not been able to biologically experience destined to seem appropriate to a present that actually calls for something else?

Poplitics

Within the exhibition Regarding Spectatorship we meet the most quoted and sampled musician of all time in Hip-Hop culture, Gil Scott-Heron, with the song The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. This song functions as a reminder (if needed) that Hip-Hop is – before being the most advanced form of Pop music – an emancipatory engine. Adapting the oral tradition of storytelling to the contemporary needs of recorded archives, and keeping up the legacy with Funk music as much as with Soul, Jazz and Blues before them, Hip-Hop has been the soundtrack of several political movements in defence of African-American culture and racial equality, but more generally the lower classes, the forgotten. Moreover, it is exactly because “Hip-Hop created a culture that rewrote the rules of the new economy”7, that it also modified our understanding of contemporary politics, offering a sharp view about the social and economic divide we ended up with. That said, having been commonly condemned as one of the causes of street violence and riots against the police, as well as one of the main factors in inducing drug abuse, Hip-Hop music today is often referred to as a tool of youth radicalization in Western societies.8 What if, conversely, Hip-Hop is just enhancing a process of popularization of political symbols, giving birth to the Poplitics age? Recently an image portraying black female members of the U.S. Army raised international attention: “Known as an ‘Old Corps’ photograph because it mimics historical portraits, it was nearly identical to thousands that cadets have posed for over the decades, with one key difference: The 16 women raised their clenched fists.”9 Since political activities are prohibited to persons in uniform, and the gesture has been immediately identified10 with the Black Lives Matter11 activist group, an internal investigation followed. But the scandal was shut down shortly afterwards because Mary Tobin – a mentor to some of the seniors who talked with them about the photograph – said that: “These ladies weren’t raising their fist to say Black Panthers. They were raising it to say Beyoncé”.12 Henceforth, if we take for granted that in order to reach high circulation for the proposed contents and media coverage contemporary activism welcomed the needs of the entertainment industry, why can’t the opposite be true? Isn’t Beyoncé entertainment the most evolved form of art as activism in the Poplitics age? Hasn’t Hillary Clinton stated: “I Want to Be as Good a President as Beyoncé Is a Performer”?13. Recently, in reference to Kanye West call for funding of his creative projects14addressed to Facebook CEO and Google co-founder, Ingo Niermann elaborated on the possibility for artists to coach billionaires into leading a less boring life15. But isn’t the Kanye West plea for funding the most visible attempt to start a revolution that can rebalance the social and economical divide on a larger scale?

Post-Migrational Rap

Post-Migrational Rap may be defined as all Hip-Hop production whose authors interrupted their careers as music lovers in order to become combatants, guerrillas or terrorists. Post-Migrational Rap is a label that can be applied only retroactively and only for extra-auditory reasons, meaning that it is not the typology of sound in itself that defines the musical genre. One well known artist that can be associated with Post-Migrational Rap is Denis Mamadou Gerhard Cuspert, the Berlin-Kreuzberg rapper Deso Dogg, who joined the Islamic State under the name of Abu Talha Al-Almani and was recently reportedly killed in a US airstrike near Al-Raqqah in Syria. Another Post-Migrational rapper is Abdel-Majed Abdel Bary from West London, known under the moniker L Jinny. He joined the ISIS army in Syria and has been suspected of being “Jihadi John”, namely the masked combatant with a British accent who appeared in the execution video of the American journalist James Foley. Berlin, London but also Paris probably have the best-known representative of Post-Migrational Rap – though unlike the abovementioned, none of his songs, albums or mixtapes are known. His name is Chérif Kouachi and he was one of the assailants of the headquarters of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. Through this new music genre one can better analyze the artists’ choice to reach their goal – or rather, to redefine or refine their role and functions within current society – through extra-artistic technologies related to war. Therefore Post-Migrational Rap is a neologism that should not be misunderstood as Jihadi Rap16, a controversial label applied to several propaganda audiovisual productions that make use of Hip-Hop core stylistic features to promote the Islamic State. On the contrary, as widely described, Post-Migrational Rap refers to the conscious choice of some artists to abandon music in favour of war. In specific cases the controversial Jihadi Rap label has been wrongly17 attributed to musical productions by Deso Dogg that circulated18 during the transition between the two lives – from rapper to fighter –, musical productions that actually belong to the context of Nasheed, but are confused with Hip-Hop – and therefore Jihadi Rap –because of a rhythmic oral storytelling delivered in German and further modified with vocal effects such as Echo and Delay. To better explain the differences between Post-Migrational Rap and Jihadi Rap one could also add the example of another Post-Migrational Rap artist, again from Berlin, who has never pursued Jihad in his entire life: Arye Sharuz Shalicar, the former rapper Boss Aro, now major and spokesperson for the Israel Defence Forces.19 But when, and for what reasons, does a specific art form – in this case Hip-Hop music – exceed its mandate and the artists start to have the need to move their ideas to other forms of action, specifically violent actions such as the armed struggle? This text has grown out of the idea that any superficial explanation, such as that the aforementioned artists didn’t achieve the artistic recognition they deserved and therefore opted for something more factual – like war – should be immediately dismissed. Conversely, is Post-Migrational Rap related to the fact that a specific art form ceased to be relevant within the current social and political debate? From the morestalgic perspective, and specifically with regard to the existence of a return trip in total absence of a round trip, it is noteworthy that Deso Dogg – when he first arrived in Syria – referred20 to a trip that lasted 35 years – basically, since the day he was born.

Propaghandi

The typology of lyrics produced by the aforementioned Post-Migrational Rap artists – or at least by Deso Dogg and L Jinny – is normally labelled as Gangsta Rap, which is a controversial, often homophobic and misogynist21 subgenre of Hip-Hop music devoted to the narration of gang-related criminal street life and lower class suburban anecdotes that first emerged in the USA during the late 1980s. Interestingly enough, when Gangsta Rap first emerged it was labelled “Reality Rap” to direct reference to the artist’s desire for self-representation through common understanding of a specific living experience. Reality Rap stands for a subjective portrait and accurate documentation of a shared reality that had – and still has – poor media coverage; the famous Chuck D 1989s statement22 is echoing here –”Rap music is the invisible TV station that black America never had […]”. The text you are reading could be described as a form of propaghandi, which is the wish to keep on dancing Last Night a DJ Saved my Life 23 rather than Last Night a DJ didn’t Save my Life, ‘cause she/he quit Music and move to armed struggle also exemplified by the claim: make love not war. This said, since the average journalistic description of foreign fighters is based on violence as a form of social revenge, let’s analyze the Gangsta Rap use of violence first. Was the violence that once fed early Gangsta Rap a violence in defence of social equality and fair racial politics? I would say no, it wasn’t. One could say that most of the American crimes described by early Gangsta Rap have shown African-American lower-class corps – being victims or perpetrators. Rather, as suggested by David Foster Wallace and Mark Costello in the book “Signifying Rappers”24 the violence of Gangsta Rap (and its box office success) is based on offering American white audiences a vision of the ghetto from within but – at the very same time – with the ghetto kept at a safe distance. Doesn’t this formula – a reality experienced by others but kept at a safe distance – sound inversely morestalgic? So, one could ask: was the violence that once fed the early Gangsta Rap promulgating a class war? I would say no, it wasn’t, because the emancipation of the community of origin – better living and social conditions for the people with whom one shares the hood – was quickly replaced by the formula: success equals individual economic wealth.25 It is no coincidence that Gangsta Rap is nowadays often used to trace and mythologize the poor roots and suburban origins of extremely successfully business ideas, and in doing so it is reinvigorating the American imagine of the self-made man “from the street corner to the corner office”.26 One of the most famous representatives of this narrative is the rapper and producer Dr. Dre, whose recent sale of his audio technology company Beats Electronics, to Apple for an unprecedented figure of $ 3 billion27 rekindled public interest in this phenomenon. Dr. Dre was indeed one of the co-founders of the collective N.W.A., which had a pivotal role in popularizing Gangsta Rap internationally. More recently, the story of N.W.A. has been sanctified by the extremely28 controversial29Hollywood biopic coproduced by Dr. Dre and titled – as the first and most acclaimed N.W.A. album – Straight Outta Compton.30One might say that Dr. Dre’s recent entrepreneurial activities demonstrate how a specific art form – in this case Gangsta Rap – exceeds its mandate and the artist starts to fell the need to move his ideas to other forms of action, which in this case we will generically call “innovative forms of business” related to storytelling and technology. What if the same happened to the Post-Migrational Rap artists? What if the Islamic State terroristic operations are an innovative form of business that has the formation of a new Caliphate as its unique selling point? Former Fulbright scholar, columnist, author, consultant and Chairman of the counter terrorism financing group for the Club de Madrid – Loretta Napoleoni – has spent her life on the topic of the overlap between international terrorism and money. She stated that: “The political vision of a terrorist organization is decided by the leadership, which, generally, is never more than five to seven people. All the others do, day in and day out, is search for money”31 and went on to describe the existence of “[…] another international economic system, which runs parallel to our own, which has been created by arms organizations since the end of World War II. And what is even more shocking is that this system has followed, step by step, the evolution of our own system, of our Western capitalism. And there are three main stages. The first one is the state sponsor of terrorism” also known as war-by-proxy. From Napoleoni’s book The Islamist Phoenix32, one can understand how: “[…] since 9/11 the business of Islamist terrorism has been getting stronger not weaker—to the extent that it has now expanded into the field of nation-building—by simply keeping abreast of a fast-changing world in which propaganda and technology play an increasingly vital role.”33 Here and again: storytelling and technology. Who started the storytelling then? “[…] the future Caliph’s astonishing achievements were made possible by stepping into the shoes of his globally notorious predecessor, Abu Musab al Zarqawi, whose myth of the superterrorist was itself manufactured by the Bush administration. Even more shocking is the fact that al Baghdadi borrowed from the Americans the instruments and techniques of propaganda that they had employed to construct and globally disseminate the terrifying, false mythology surrounding the Jordanian jihad leader.”34Furthermore, what kind of technology? “The successful manufacturing of the myth of al Zarqawi rests on two factors: the power of the media, which spread across the globe a terrifying message delivered by Colin Powell to the UN Security Council, and the willingness of Western citizens to believe this dubious message in the aftermath of 9/11. Just over ten years later, the Islamic State was using social media to spread a terrifying new and equally false set of myths. And, as it was a decade ago, the world seems well inclined to believe them. Al Baghdadi and his followers understand the importance of virtual life and our tendency to act irrationally when dealing with mysterious, terrifying issues such as terrorism. Showing a clear understanding of sophisticated communications analysis, they have invested extraordinary energy in social media to spread frightening prophecies, in the knowledge that they will have a self-fulfilling effect. They also seem perfectly conscious that in a world where the twenty-four-hour media cycle has turned journalists and readers into junkies of shocking and extraordinary events, the truth value of an account takes second place to its shock value.”35

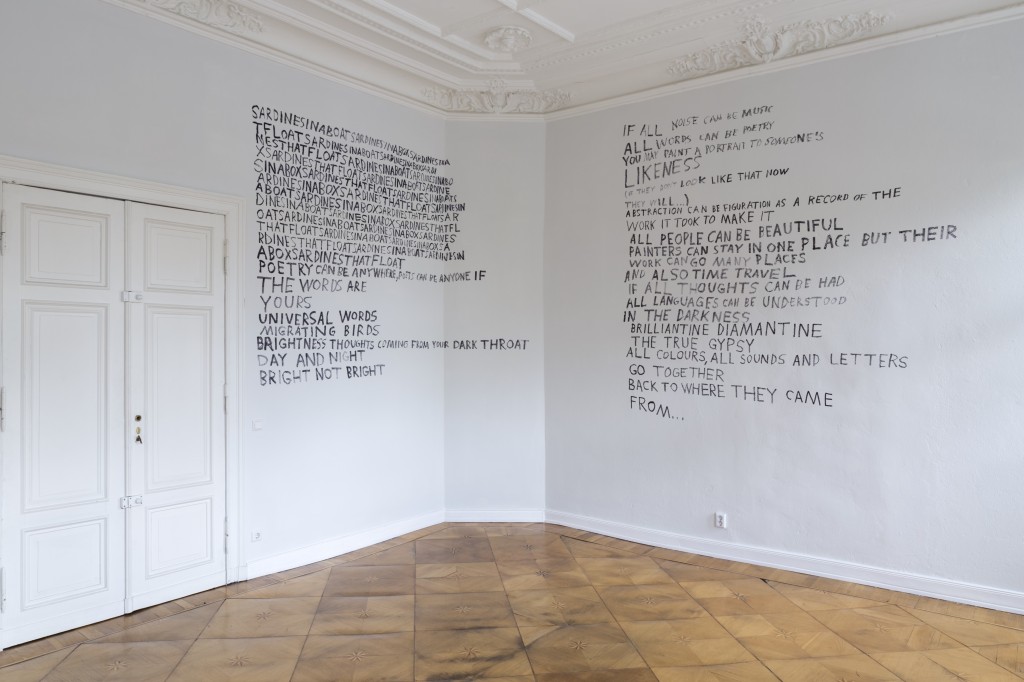

Liam Gillick, Half a Complex, PowerPoint presentation, Video projector, box,

Wall with opening and soffit (optional), 2014

Concllusion

“A view from this remove yields easy abstractions about rap in its role as just the latest ‘black’ music. Like: the less real power people have, the more they’ll assert hegemony in areas that don’t much matter in any grand scheme. A way to rule in hell […]” .36 So, are we artists ruling in hell only? Is that our role within present-day society? Are we all agreeing upon the fact that art is an area that doesn’t much matter in any grand scheme? Is that the reason why it is fine to think that some artists – in order to widen their actual agency – need to implement extra-artistic operations? Furthermore, does art as activism, or activism as art, imply that art is not enough to propel a change? Are we artists stuck with a model based on the idea that helping those who have real global needs is better than starting from our neighbours and fellows? Wouldn’t it be better to deploy an everyday practice of empowerment and self-awareness enhanced by art? It is all too easy to employ the excuse of genius to conceal the inability to feel empathy. But isn’t charity simply the most efficient form of marketing in an empathy fuelled economy? Is that the reason why Kanye West twitted to Google co-founder Larry Page to start funding his own creative projects rather than “[…] open up one school in Africa like you really helped the country…”?37 Don’t we human beings all come from Africa? Isn’t – after all – helping a school in Africa a bit morestalgic? We know you business people working in the creative/entertainment industry would label as anti-conventional what we would call art! But that may be a first real meeting point – especially in time of Poplitics – because we are referencing the exact same meaning, a change of pace, with no need for an already existent type of storytelling or technology. Any kind of improvement can only be the result of long-term cooperation between different instances. Therefore, rather then transforming the Museum into a space for new educational models, for example, I would propose more and more artists teaching in schools without leaving their art behind – bringing art into the classroom, or even transforming the classroom into art. Rather than mocking the aesthetics and processes of the new economy in exhibition spaces, I would propose more and more artists becoming CEOs of enlightened forms of entrepreneurship and still having the will to produce art. Rather than artists proposing highly digestible forms of meta-activism, I would love to see them seated at the desks of several Democracies – to discuss mainly art of course.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Marianna Liosi and Boaz Levin for commissioning this text, and moreover for propelling a needed and fundamental discussion with the show and research project Regarding Spectatorship. This text is an expanded upgrade of a previous version titled Sicilia Bambaataa and published by NERO publishing38 on the occasion of the homonymous exhibition curated by Laura Barreca for Museo Civico in Castelbuono, Sicily, 2014. Post-Migrational Rap and other neologisms have been previously selected by Raimundas Malašauskas for the publication HR – Sommerakademie Im Zentrum Paul Klee in 201439 and further translated into Polish and included by Aneta Rostkowska in the show All Mounds Can Be Seen From My Window at Bunkier Sztuki Gallery of Contemporary Art in Cracow, 2015. Also, thanks to Adrian Piper’s Funk Lessons40, thanks to curator Maurin Dietrich for helping me discover the case study of Boss Aro, thanks to curator Myriam Ben Salah for pointing out Oliver Roy’s concept of Islamisation of radicalism rather than radicalization of Islamism41, thanks to Creamcake for their parties in Berlin through which I’m constantly questioning my understanding of Hip-Hop and thanks to my students for keeping on endorsing and inventing the use of neologisms in daily life.

| 1. | ↑ | Robert Henke in conversation with Stefan Goldmann, Presets – Digital Shortcuts to Sound, The Tapeworm, 2015, p. 42 |

| 2. | ↑ | With the body of works titled Phonemenology, I’m currently researching a structural shift in phenomenology and how the daily use of smartphones could affect the role of the human body as interface within a constructed environment as much as the role of a subject as interface within a Democratic State. |

| 3. | ↑ | I specifically refer here to the symbol of “truth” offered by the narrative that every human being / prosumer makes of himself, also known – on a different scale – as branding. |

| 4. | ↑ | https://tiqqunista.jottit.com/notes_on_the_local |

| 5. | ↑ | Riccardo Benassi, Attimi Fondamentali, Mousse Publishing, 2012, p. 109 |

| 6. | ↑ | “For this reason technological interactivity, seen from here, is a myth. It proposes to circumscribe the solutions by numbers – leading to the belief that some problems may be eliminated by doing so, in practice – this is nothing but the revival of the eldest method of total cancellation of minorities – that method which dehydrates life from the rivers of fear and from the vortexes of the incalculable. In a work context – this method results in the infinitesimal fragmentation of professions and professionalisms. This way each category or field of knowledge can refer to other categories or fields of knowledge for the research of a satisfactory result every time a doubt or hypothesis is likely to question its internal logic. In practice, we are constantly deferring – and in doing so – we end up in the depths of a constant and pathological desire to forecast. To wonder what will happen is the easiest method, in practice, to forget what is happening.” Riccardo Benassi, Techno Casa, Errant Bodies Press, 2015, pp. 20-21 |

| 7. | ↑ | Steve Stoute, THE TANNING OF AMERICA: How the Culture of Hip-Hop Rewrote the Rules of the New Economy, Avery, 2012 |

| 8. | ↑ | “European government officials are increasingly worried about the influence that Muslim rap artists wield over youth, and are scrutinizing hip hop practices in poorer immigrant neighbourhoods, trying to decide which Muslim hip hop artists to promote and which to push aside.” Hisham Aidi in Cicero Magazine, http://ciceromagazine.com/features/is-extremist-hip-hop-helping-isis/ |

| 9. | ↑ | http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/07/us/raised-fist-photo-by-black-women-at-west-point-spurs-inquiry.html?_r=0 |

| 10. | ↑ | http://www.inthearenafitness.com/index.php/racism-within-west-point? |

| 11. | ↑ | blacklivesmatter.com |

| 12. | ↑ | http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/07/us/raised-fist-photo-by-black-women-at-west-point-spurs-inquiry.html?_r=0 referencing both the song Formation by Beyoncé and the Halftime Super Bowl performative presentation of it https://youtu.be/c9cUytejf1k?t=7m5s |

| 13. | ↑ | http://time.com/4153621/hillary-clinton-beyonce-iowa-town-hall/ |

| 14. | ↑ | http://www.mirror.co.uk/3am/celebrity-news/mark-zuckerberg-responds-kanye-wests-7391550 |

| 15. | ↑ | The Proxy, Ingo Niermann, Mousse Magazine, Issue#53, April-May 2016, pp. 168-172 |

| 16. | ↑ | http://foreignpolicy.com/2013/04/29/9-disturbingly-good-jihadi-raps/ |

| 17. | ↑ | http://edition.cnn.com/2013/11/18/opinion/bergen-rapping-al-qaeda/index.html |

| 18. | ↑ | https://youtu.be/FmpaKaWKSkc |

| 19. | ↑ | https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arye_Sharuz_Shalicar |

| 20. | ↑ | https://youtu.be/f0gFfXDgrD8 |

| 21. | ↑ | The highly misogynist and homophobic perspective of Rap music has been completely shattered in the last decade by the progressive development of the musical subgenre known as Gay Rap. This label is problematic for many artists because of its inherent tendency to link a cultural form to personal sexual orientations. But the presence within Rap music of LGBTQ Rap artists or not, artists interested in developing an alternative vision of women and homosexuality within current society, must in our view be hailed as revolutionary. |

| 22. | ↑ | 1988 September, SPIN, Volume 4, Number 6, Armageddon in Effect, Interview by John Leland, Start Page 46, Quote Page 48, Column 1, Published by SPIN Media LLC. |

| 23. | ↑ | https://youtu.be/_dKlLHE6sMQ |

| 24. | ↑ | David Foster Wallace & Mark Costello, Signifying Rappers, Penguin Books, 1990 – 2013 |

| 25. | ↑ | “[…] ‘freedom’ becomes not qualitative but quantitative, quantifiable, a cold logical function of where you are and what you have to exercise it on. […] Little wonder that in rap the constitutional watchwords of white public discourse detach, emptify, float: oh Jesus surely freedom can’t be just the wherewithal to buy and display.” Ibid. p. 137 |

| 26. | ↑ | Zack O’Malley Greenburg, Empire State of Mind: How Jay-Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office, Portfolio, 2012 |

| 27. | ↑ | http://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolomon/2014/05/28/apple-brings-dr-dre-on-board-with-official-3-billion-beats-deal/#4cd43f5e16d2 |

| 28. | ↑ | https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/nov/02/nwa-manager-jerry-heller-files-110m-straight-outta-compton-libel-suit |

| 29. | ↑ | http://pitchfork.com/news/60843-dee-barnes-and-michelle-speak-out-about-dr-dres-abusive-past-exclusion-from-straight-outta-compton/ |

| 30. | ↑ | in 1990 David Foster Wallace & Mark Costello wrote: “Soon Rap publicist will face a problem their porn counterparts encountered over a decade ago. Every single shocking act of sex or pain will have been ‘done’ symbolically, and, in the process, rap’s audience will have acquired a taste for bloody novelty. The result: our first ‘snuff’ rap record, which, rumour will have it, an actual person died making. Editorial writers will be appalled, giving the new snuff rappers the kind of jackpot of free publicity N.W.A. enjoyed in the spring of ’89.” And their ironical forecast came actually true in the making of the N.W.A. movie, where one person has been allegedly killed on set by Suge Knight: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/feb/02/suge-knight-murder-accident-straight-outta-compton |

| 31. | ↑ | https://www.ted.com/talks/loretta_napoleoni_the_intricate_economics_of_terrorism |

| 32. | ↑ | Loretta Napoleoni, The Islamist Phoenix, The Islamic State and the Redrawing of the Middle East, Seven Stories Press, 2014 |

| 33. | ↑ | ibid. p. 5 |

| 34. | ↑ | ibid. p. 58 |

| 35. | ↑ | ibid. p. 61 |

| 36. | ↑ | David Foster Wallace & Mark Costello, Signifying Rappers, Penguin Books, 1990 – 2013, p. 76 |

| 37. | ↑ | https://twitter.com/kanyewest/status/699108449561526272 |

| 38. | ↑ | http://www.neromagazine.it/n/?page_id=20441 |

| 39. | ↑ | http://www.sommerakademie.zpk.org/en/publications/publications/single-view/article/hr.html |

| 40. | ↑ | http://www.adrianpiper.de/vs/video_fl.shtml |

| 41. | ↑ | http://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2015/11/24/le-djihadisme-une-revolte-generationnelle-et-nihiliste_4815992_3232.html |