At the end of nineteenth century, Gabriel Tarde helped bring about a radical shift in the terms of the academic debate on the nature of social psychology, when he said: “I therefore cannot agree with that vigorous writer, Dr. Le Bon, that our age is the ‘era of the crowds’. It is the age of the public or of publics – and that is a very different thing….” And again, “one cannot deny that it [the public] is the social group of the future.”1 With the brilliant intuition of an epoch-making shift, Tarde concentrated on the public as a key entity from both a theoretical and a historical point of view, the definition of which entails a re-discussion of some of the fundamental aspects of the relationship between singularities and collective subjectivities. But can an intuition dating back over a century still be considered relevant today?2 Just over a year from the opening of Expo 2015, projections and estimates are being churned out as to the potential number of visitors who will arrive in Milan for the event. The ambitious goal is to exceed the 73 million who visited the Chinese Expo between May and October 2010. The European Commission uses the term audience development to refer to a theme that cuts across the entire Creative Europe programme (2014-2020) and has been allocated a total budget of €1.4 billion. According to Forbes magazine, the Brazilian government has invested about $11 billion in the 2014 FIFA World Cup (the most expensive in history, in a country with some of the greatest class divisions in the world). The re-election of Dilma Rousseff’s Partido dos Trabalhadores in the national elections in October is in the hands of the yellow-and-green Seleção football team. In the meantime, the pacification of the revolts of those who refuse to become the public of the World Cup has once again been entrusted to the military police.

Tarde viewed the French Revolution as the historic moment that asserted the public as a new social group (“The true advent of journalism, hence that of the public, dates from the Revolution, which was one of the growing pains of the public….”3), while Guy Debord’s radical critique of the “spectacular order”4 came just before the revolution of May ’68. As a category, the public runs through the entire history of bourgeois democracies and cuts across all its socio-political reconfigurations. As Maurizio Lazzarato recalls, “its genealogy is directly linked to the need to establish policies for the control of the subversive (anarchist and trade-union) actions that exploded in France in the late nineteenth century.5

Benjamin’s concept of exhibition value clearly renders the two-fold division between spectacle and exploitation in the indistinction/reversibility of perception and work.6 Similarly, workers at the universal exhibitions in the late nineteenth century were asked to admire what to them was work (exploitation) as public (spectacle). Today, in the so-called creative/cognitive job market, which is the most unequal and competitive of all, work is requested in exchange for mere visibility, to make oneself known. This is a “parodic end of the division of labour”, 7 as Debord would have said, which the information economy has skilfully managed to put to work through interconnecting networks, consistently reconfiguring it in order to achieve an increase in productivity.

It is thus not merely a coincidence that the 2015 Milan Expo has chosen the symbolic 1 May as its opening date. The extraordinary reforms introduced by the Renzi government’s Jobs Act use this showcase as a means of legitimising a reform of the labour market (structural precariousness and the promotion of voluntary work) that comes at the tail end of the process of dismantling workers’ rights which began in the early eighties. The hard-fought achievements of the labour movement in Italy have now been permanently lost.

If it is true that the spectacle “reunites the separate but reunites it as separate”, 8 then it will be necessary to construct new forms of political action that are able to break away from the government of publics. A move in this direction can be seen in the present attempt to draw an articulation that is inherent to the publics as a social group and to isolate some of their elements. These may constitute a sort of toolbox for future reinterpretations, critiques and deconstructions.

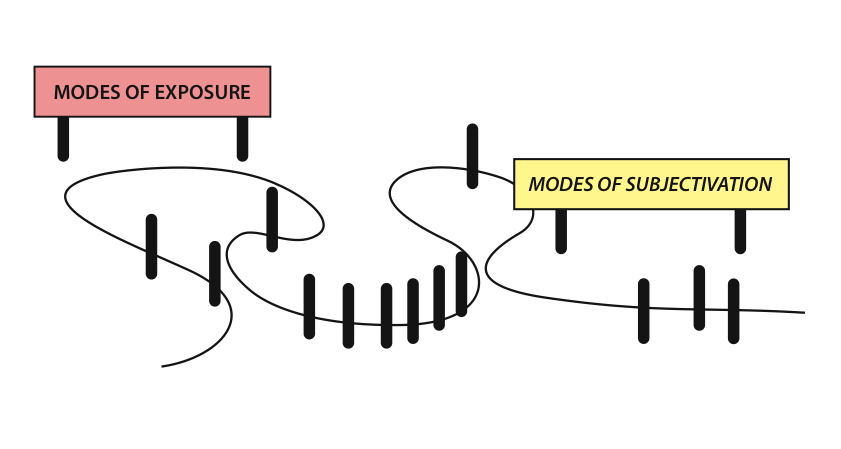

The following contribution, which has been drafted together with the artist Falke Pisano, attempts to analyse the division between modes of exposure and modes of subjectivation of publics by means of a series of diagrams. Here the diagram represents more an open form of argumentation of the discourse than a complete statement in itself. Since they are a form of visual rather than representative communication, diagrams tend to pose questions rather than come up with direct answers. In view of the complexity of the subject, it has however been considered advisable to assist interpretation of the signs with short texts which, in any case, are no more than possible interpretations of the diagram itself.

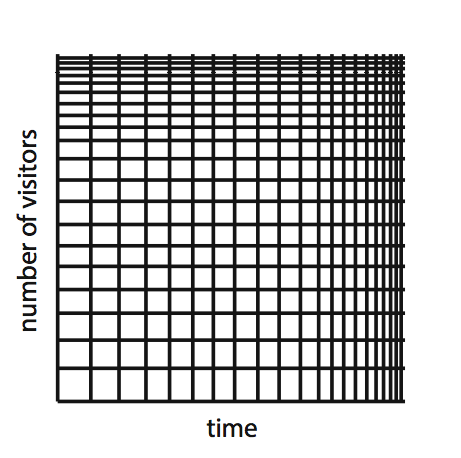

1. The coefficient of value

In an economy based on the so-called exhibition model, whether it be a biennial, an exhibition, an online or printed newspaper, a festival, a web site or whatever, the economic value of what is on display is calculated using the formula number of visitors / exhibition time. In the diagram, the number of visitors increases towards the top, while the period of time considered gradually decreases as it moves to the right. The corner where the intersecting lines become closer, and the area they delimit decreases, represents the coefficient of greater exhibition value. This cannot be established at some extreme limit, but is placed on a vector with a progression that is virtually infinite, like the subdivision of the surface into molecular particles. The only real limit is that of the image or of our ability to perceive it.

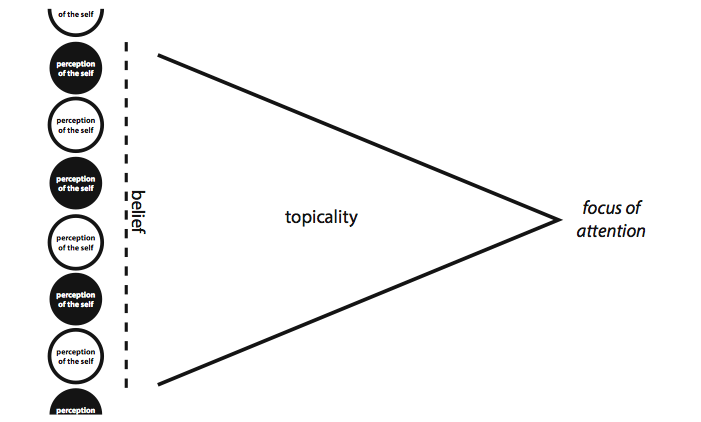

2. Modulation of attention

The constitution of a public is given by the intensity of time rather than by the size of the space. Its form of uncertain, scattered, mediatised subjectivation corresponds to a regulation that can no longer act by means of securitarian devices (distance or containment), as in the case of the crowd or the population, which are organised in space, but rather by means of a control that places the publics in temporal sequences, defining its own frequency and describing its trends. The public can be controlled only in an open space, where the flow of information and the elements that constitute it – time, velocity and remote action – are regulated. Modulating attention thus exerts the government’s action.

3. The topicality of publics

The bond that forms the public is radically different from the one that forms a crowd. In the public, the set of psychic contagions does not depend on physical contact, but is defined as the “action at a distance of one mind upon another” (Tarde). 9 Communication technologies individualise and separate bodies but, at the same time, through their remote action they bring into play a new type of spiritual connection. The bond that unites publics is the conviction of each individual that a particular idea or desire is simultaneously shared by a large number of other people. For example: we avidly read a news item in a newspaper or on a web page, only to realise that it was written a month ago or yesterday and our interest in it suddenly disappears. This particular temporal dimension and power to regulate our attention – which is its topicality – brings into play the complex relationship between the one and the many. This is the distinctive feature of the public as a social group: the greater the size of the public reached by a certain news item, event or fact, the more the latter will be deemed or felt to be topical.

The device for governing publics also involves this control of time: the expansion of topicality as a single temporal dimension of what is sensible corresponds to the elimination of any historical consciousness, which is now definitively banned. While fashion is proud to follow the seasons, topicality is measured in terms of hours, sometimes even seconds. News increasingly rushes in with information constantly updated, condemning us to live in an eternal present, in a “world without memory, where images flow and merge, like reflections on the water” (Debord). 10

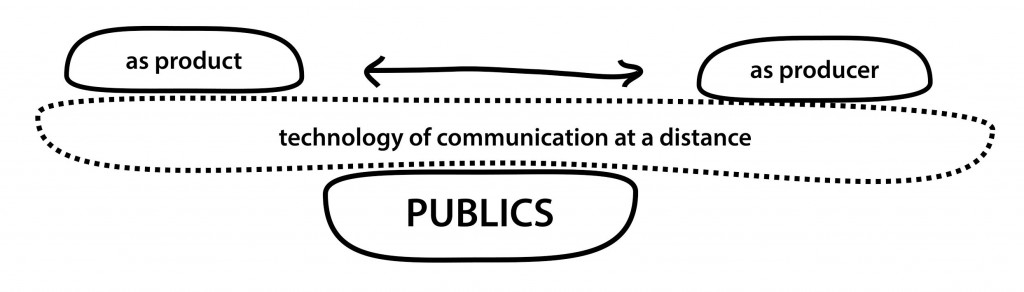

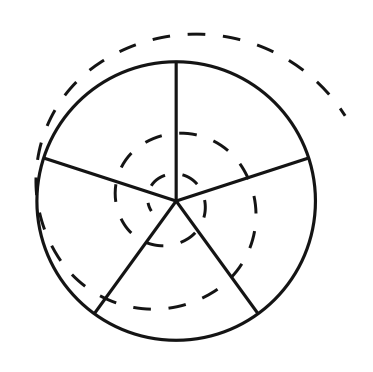

4. The articulation of publics

Several aspects of the concept of the public have been formulated during the course of history: from the audience of poets and men of letters in Ancient Greece, to the spectators of cinema or television in the modern era. The term prosumer (producer-consumer) emerged in the post-Fordist era with the development of service networks that turn feedback from users into value. Today we often hear the term productive publics in reference to the active participation of a particular community in all levels of the production cycle. These different degrees of passivity/productivity in the constitution of different publics may be associated with the technological changes that have led to their introduction (from the visual-auditory device of the body through to the prostheses of interconnection, which constitute multiple, fragmented subjectivities). In this sense, the forms that constitute the public as a “product” and as “producers” can be located at the two ends of a line indicating technological transformations.

However, the articulation of the relationship between public and technology, and between public and subjectivity, has yet to be examined from a point of view that takes into consideration the modulations of time and memory. In this case, it might no longer appear as a finalised historical fact, with a beginning and an end, but rather as a tendency, which is to say, as an event.

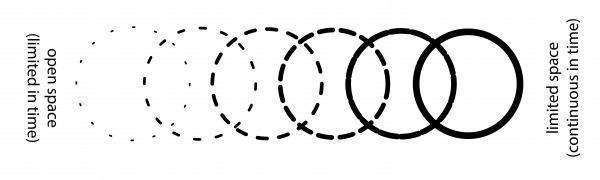

5. The gradient of expansion and inclusion

The virtually unlimited extensibility of publics 11 is due to: 1. Their degree of deterritorialisation; 2. The effects of remote communication technologies; 3. The presence and creation of publics in time, rather than in space. At any given time, one can indeed be part of only one crowd, one population, and one assembly, but one can belong to a number of different publics at the same time. A public does not take the place of pre-existing social groups, but is superimposed upon them, due to its power and speed of expansion. “It seems to us that the public can be defined as the most dynamic and deterritorialised of these models, that therefore will tend to command and reorganise the others.”12 Mediatised subjectivities generate multiple, fragmented processes of belonging, the random form of which constantly moves forward in an acceleration in which there is no intensification of the relationship or of subjective experience. On the contrary, it negates them.

While territory and space play a key role in bringing about social striation in publics (based on class, gender, race, etc.), it is the number, and thus statistics and the curves of time that define the degree of discriminating value. In this sense, we see a possible identification of publics with economic value that, with Benjamin, we might call the exchange value. It is no coincidence that statistics showing the number of visits and online contacts which are systematically generated at the end of any large-scale event or festival are the only way that promoters and sponsors of the event have to assess its success in economic terms.

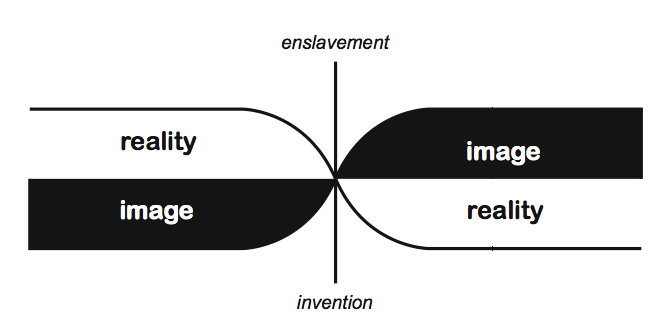

6. The process of reversibility

The tendency towards the reversibility of the real and the imaginary, object and image, essence and phenomenon, has been addressed by the Situationists and theorised as a “society of the spectacle”: “the ‘becoming-world’ of falsification was also a ‘becoming-falsification’ of the world” (Debord).13 The limitation of this analysis, however, is in interpreting the possibility of a reversal of signs and forces only as a subordination of all reality to the spectacle, which is to say to Capital. The point of contact between signs and reality actually marks the threshold of possible worlds, in which enslavement and political invention are two opposing variables of the same tendency.

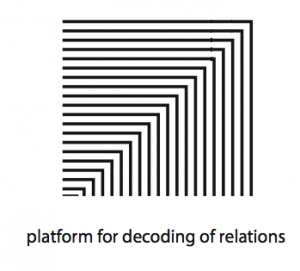

7. Visual and auditory bonds

In 1926, Dziga Vertov theorised a platform for a (communist) decoding of world relations, starting out from the visual and auditory bonds brought about by the new “kino-eye” machine.14 The creation of these bonds was the premise for a common perception among the proletariat of the world, which would pave the way for the success of the revolution. In this sense, Vertov was pointing to the subversive potential that is inherent in the production of the public. Prior to Vertov, it was Gabriel Tarde who had had the same intuition, interpreting the massive circulation of newspapers in Paris as the new phenomenon that had led public opinion to prevail over traditional forms of government just before the 1789 Revolution. The circulation of low-resolution images on the web (file sharing, YouTube, mobile phone cameras, social networks, etc.) was one of the key features of the new cycle of struggles that began in 2008 (Brazil, Turkey, Greece, Spain, Egypt). As the artist Hito Steyerl reminds us, in a certain sense Vertov’s dream has come true today, although mostly “under the rule of a global information capitalism whose audiences are linked almost in a physical sense by mutual excitement, affective attunement, and anxiety.”15 From a historical point of view, the circulation (or its opposite, the blockage) of signs, images, statements, and the social and perceptual ties it brings about can be translated no less as the strength of alternative political organisations than as the coding and control of Capital over reality.

Paolo Caffoni is an editor and writer. He is Associate Editor of the publishing house Archive Books (Berlin) and Edizioni Temporale (Milan). He teaches at NABA–New Academy of Fine Arts Milan. His writings can be found in No Order magazine, Art Metropole, Nolens Volens, Alfabeta2, Uninomade, Commonware among other publications. Since 2012 he has participated in the activities of Macao, New Centre for Arts, Culture and Research Milan.

Falke Pisano is an artist based in Berlin. Pisano’s artistic practice focuses on the relationship between opposing and complementary poles such as language and body. In these terms, the two principal series of works by the artist (Figure of Speech, 2006–2010, and Body in Crisis, 2011– on-going) are reflections on the disjunction, reproducibility and reconstruction of the act of speech and the corporeal realm. Pisano’s solo exhibitions include Praxes, Berlin (2014), The Showroom, London ( April 2013).

| 1. | ↑ | Gabriel Tarde, “The Public and the Crowd,” in id., On Communication and Social Influence: Selected Papers, ed. Terry N. Clark (Chicago/IL: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 281. |

| 2. | ↑ | The present text has been written in June 2104. In spite of Dilma Rousseff re-election and the drastic redrafting of the expectations regarding the Milan Expo, I still consider the thesis that follow as valid. |

| 3. | ↑ | Ibid., 280. |

| 4. | ↑ | Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Black & Red (Detroit/MI: Black & Red, 1970 [1967]), Thesis 8 https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/debord/society.htm (accessed 2014-08-09). |

| 5. | ↑ | ”Maurizio Lazzarato, “Per una ridefinizione del concetto di ‘bio-politica’,” in “Lavoro immateriale. Forme di vita e produzione di soggettività”, (Verona: ombre corte, 1997), 117: “It is clear what enormous difference separates this definition of ‘public’ from Habermas’ concept of ‘bourgeois public sphere’.” |

| 6. | ↑ | Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in id., Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969 [1936]), 217-251, 224, Thesis v http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ge/benjamin.htm. |

| 7. | ↑ | Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, trans. Malcolm Imrie (London and New York: Verso, 1998 [1988]), 10, Thesis IV. |

| 8. | ↑ | G. Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, op. cit., Thesis 29. |

| 9. | ↑ | Gabriel Tarde, “Preface to the Second Edition,” in id., The Laws of Imitation, trans. Elsie Clews Parsons (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1903 [1895]), xiv. |

| 10. | ↑ | G. Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, op. cit., 14, Thesis VI. |

| 11. | ↑ | G. Tarde, “The Public and the Crowd,” op. cit., 281. |

| 12. | ↑ | Maurizio Lazzarato, op. cit., 120. |

| 13. | ↑ | G. Debord, Comments, op. cit., 10, Thesis IV. Translation modified, from: “the globalisation of the false was also the falsification of the globe.” |

| 14. | ↑ | Dziga Vertov, Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O’Brien (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984). |

| 15. | ↑ | Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” e-flux, journal #10 (November 2009) http://www.e-flux.com/journal/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/ (accessed 2014-08-11). |